“You can kill the revolutionary but you can’t kill the revolution!” These were some of the most powerful, eerily foreshadowing, and sobering words of the most recent blockbuster movie, Judas and the Black Messiah. The movie chronicled the plot to assassinate the chairman of the Chicago chapter of the Black Panther Party, Fred Hampton, Sr. Indeed. “revolutionary” was the perfect word to describe this man, and “revolution” was the perfect word to describe the movement he catalyzed.

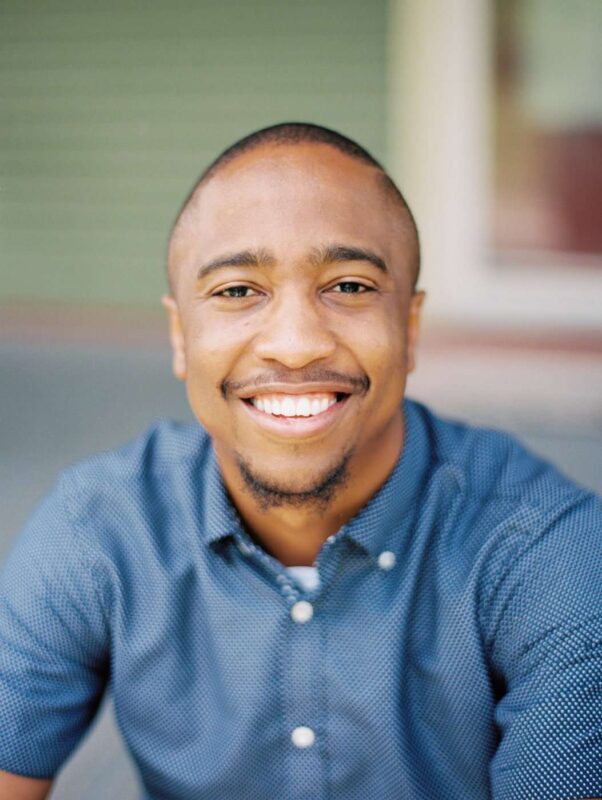

During the same time Fred Hampton was being hunted down by the government for his controversial speeches, another fiery orator was haunting the minds of evangelicals with his “controversial” sermons.(1) Tom Skinner was his name. Skinner is one of the most important figures of last century too many people don’t know about. Born the son of a black minister, he was involved with one of the largest gangs in Harlem before God rescued him on his way to a massive Boston Tea Party-like brawl.(2) That day would be the beginning of a revolution that would begin in the heart of one man but would spread across the United States like the great fire of 1776.

Tom Skinner devoted his life to preaching the Kingdom of Jesus Christ to the masses—and preach he did. He was tagged with the nickname, “the black Billy Graham,” though he admits there were differences in their preaching. Skinner, as he said, went to the impoverished communities, while Graham went to “middle America.”(3) Though they had the same goal, they had very different targets. And while Skinner was noticeably different from Graham, he wasn’t the typical black preacher either. His style was far more conversational, and he even poked fun at some black preachers (in ways that he would later admit were not helpful) who would change their voice and put on their preacher “persona” as they got in the pulpit. Though his delivery was just as fiery as the typical black preacher, in some ways he connected more than others with the inner-city community. He used slang like “jivin,” referred to Bible characters as “cats,” and even gave nicknames to some of faith’s heroes. As his book title states, he was Black and Free and never felt the need to trade in one to salvage the other. His ministry was formative for young black men like Tony Evans, Crawford Loritts, Carl Ellis—all men who pay tribute to the impact Skinner had on their lives and ministries and who deserve their own articles of recognition.

But it wasn’t only his audience and delivery that separated Skinner—it was his content. He was often too “street” to preach in black churches, and too justice-oriented to continue his circuit in mostly white evangelical affiliated institutions. Like today when many shy from phrases like “Black Lives Matter” out of fear of who it associates them with, so also in Skinner’s day words like “Black Power,” “the System,” and “Revolution” terrified some who assumed that those who used such words were “too social” and had no place in the church. For Skinner, however, this posed no problem. Not only did he sympathize with Words of Revolution (the title of one of his greatest books), he employed revolutionary language throughout his sermons. He would preach as though a “takeover” of all the world systems was immanent, and he would prepare his comrades by using such language as “sabotage” and even calling them “Kingdom saboteurs” who were called to “infiltrate the world systems” and lay them to rest on behalf of the Kingdom of God.(4) The weapons of this revolution, however, were not AK-47’s, pistols, and billy clubs like that of the world. Instead the weapons were the Sword of the Spirit, the atom bomb of an authentic life, and the grenades of grace that would overturn the systems because they would transform the hearts of system adherents. Equipped with this armor, Tom Skinner envisioned a full-takeover of the world systems by God’s eternal Kingdom and therefore powerfully spoke against both religiosity and racism, anarchy and pacifism, radicalism and nationalism, personal immorality and social injustice. He was a revolutionary preacher who was not bound by any party, tribal affiliation, or traditional mandates. After all, what is a revolution if it is not a fight for freedom? And this preacher fought for freedom by preaching freedom freely.(5)

About a year after Fred Hampton was murdered in Illinois, Skinner, the other revolutionary, delivered one of his most powerful sermons in the same state at the Urbana Conference in 1970. At a conference that featured the likes of the great John Stott, he not only captivated the audience but challenged evangelicals to confront racism as revolutionaries in their own day in light of historic racism. It was a sermon well ahead of its time, though it may have created even more distance between him and the white evangelical church. It took courage, and the courage paid dividends that we might never fully comprehend.

So what gave Skinner courage to preach this kind of message? What gave him hope that a revolution was indeed brewing? It was the fact that Skinner didn’t claim to be a revolutionary in and of himself. Hear these words again: “You can kill a revolutionary but not a revolution.” These words from Hampton are optimistic but in so many ways not realistic. The sad reality is that many movements die shortly after the death of its greatest leader. Look at what happened to The Nation of Islam after the death of Malcolm X; or the Universal Negro Improvement Association after the death of Marcus Garvey; or the Black Church-led Civil Rights Movement after the death of Dr. King; and even the Chicago Chapter that Hampton headed up dissolved only a few years after his death. Revolutions sadly often die with the death of a prominent revolutionary.

But the late great Tom Skinner wasn’t his own revolutionary. He claimed to be part of a far greater revolution and led by a far greater Revolutionary—Jesus Christ. This Revolutionary would call His people to be, yes, radical. This Revolutionary would indeed overturn world systems by the prowess of His adherents. And, sadly, this Revolutionary would also be assassinated. But the major difference is that unlike Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey, Dr. King or even Fred Hampton, Sr., the Revolution of Tom Skinner wouldn’t slowly die out after Christ’s death. No, in fact, it would rise with even more power than it had before. How could this ever be? It is because this Revolutionary, the Revolutionary that Tom Skinner committed his life to preaching, rose to life three days after His assassination. You might be able to kill a revolution by killing a revolutionary; but you can’t kill a revolution if the Revolutionary won’t stay dead!

Even though Fred Hampton’s legacy might seem to have trumped Skinner’s in terms of popularity, ultimately the revolution Skinner was committed to will go on because the True Revolutionary he preached does. So this Black History Month, may we honor the legacy of the great Tom Skinner, by going out as saboteurs, or dare we say “revolutionaries,” to the glory of Christ, and the good of the world.

- (1) New York Times, “Controversial Black Preacher Putting Stress on Social Issues,” New York Times, September 2, 1973, available at https://www.nytimes.com/1973/09/02/archives/controversial-black-preacher-putting-stress-on-social-issues.html.

- (2) Tom Skinner, Black and Free (Maitland, FL: Xulon Press, 2005).

- (3) New York Times, “Controversial Black Preacher.”

- (4) Tom Skinner, “The New Community,” Jesus ‘73 conference sermon, Morgantown, PA, June 1973, available at https://youtu.be/uFAmzdSW7sY.

- (5) Tom Skinner, Words of Revolution: A Call to Involvement in the Real Revolution (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1970).

Prayer Requests:

- Pray that today we would learn how to so know the story of the Scriptures that we would be able to ‘translate’ it into the language of culture today.

- Pray that we would be more committed to winning the lost to Christ, than winning the ‘found’ to our particular tribe.

- Pray that we would commit to being a community that “turns the world upside down” like true Revolutionaries.