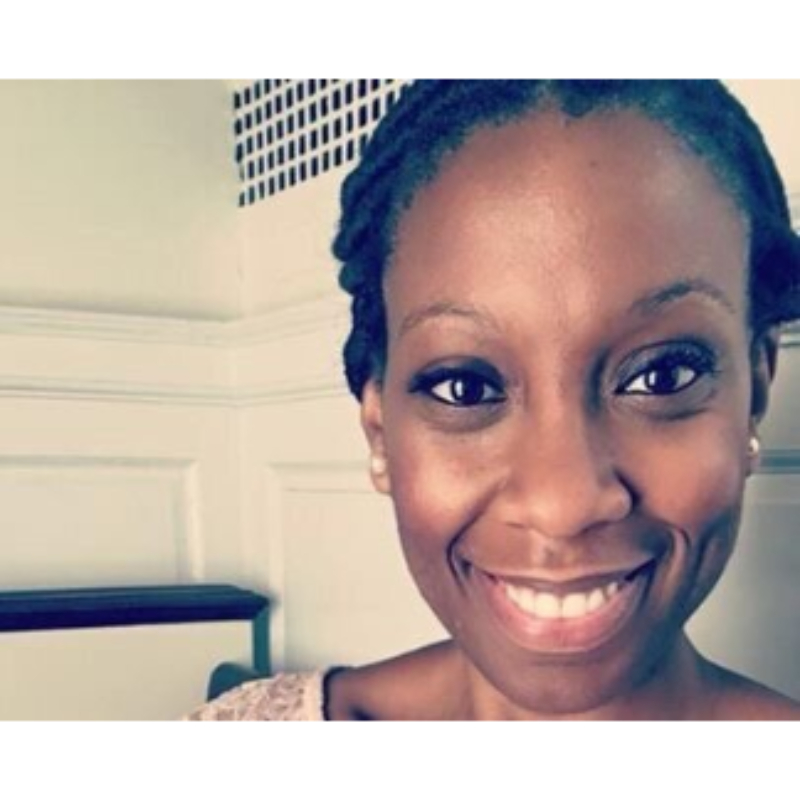

I came late to loving my skin. I was the fairest-skinned in my family and they teased that if I stayed outside for too long, I’d become as dark as they were and never fade. So I avoided sunlight. I’d bought into colorism—the idea that the lighter your skin the better. That’s was the start of When I Recognized Race.

I grew up in a military family. After short stints in Kansas and Japan, I spent my early elementary years in Michigan. My friends were mainly white and, for the most part, I felt at home with them while also knowing in a superficial way I was different. My first crush was my white neighbor and I remember my sister telling me white boys didn’t like black girls.

In fourth grade we moved to Virginia. Although I could’ve rooted myself within a black community, being shunned by them as too culturally white to fit in deterred me. Black people accused me of being an Oreo (black on the outside but white on the inside), but I was just me: a girl who’d lived in three states and two countries by the time she was ten and hated the sun. I felt unavoidably and painfully black.

I naively thought I could accomplish my way into blending in among whites. It was less uncomfortable to be too black for my white friends than to be too white for my black ones. I was disillusioned after my boyfriend’s mother called me “lazy like all black people.” (She said this because I had an opportunity to perform at Carnegie Hall but wasn’t taking it due to a schedule conflict). He later admitted he knew she was racist and pressure from her contributed to our eventual breakup.

God delivers in strange ways. Through moving to Laos after graduate school, at 28 I finally learned to love my skin. Lao people are many-hued and I found myself admiring the darker of their skin tones. Through seeing the beauty of their skin, I began to see my own.

I began reckoning with the words of Malcolm X:

Who taught you to hate yourself? Who taught you to hate the color of your skin? Who taught you to hate the texture of your hair? Who taught you to hate the shape of your nose and the shape of your lips? Who taught you to hate yourself from the top of your head to the soles of your feet?…You should ask yourself who taught you to hate being what God made you.

I also wrestled with the words of God: he’d knit me together and I was wonderfully made (Psalm 139:13-14), he determined the times and places I’d live (Acts 17:26), part of the glory of heaven itself would be its diversity (Revelation 7:9), God detests dishonest weights and measures (Proverbs 11:1)—in ascribing value to people as well as in commerce, human sight was deceptive in judging each other (1 Samuel 16:7), God gave greater honor to the parts that lacked it (1 Corinthians 12:24), we do not make ourselves beautiful the way the world does (1 Peter 3:3).

The evidence was overwhelming. Who was I to refute my maker?

One of the biggest areas I’ve had to learn to trust God with over the years is believing he didn’t make a mistake or limit my possibilities for flourishing by making me black. He made this deliberate design choice while keeping in mind my highest good and his promise of life abundant. My blackness does not preclude me from those but invites me to them. I had thought being black held me back but, in some ways, it has given me a greater sensitivity to and awareness of the outcast, marginalized and weak. My perpetual otherness has primed me more easily for empathy and I am a steward of the sensibilities that gift endows.

I’ve also learned to be on alert for making assumptions of my neighbor based on the assumptions I fear they’re making of me. I need to keep vigil over my own heart for unforgiveness, bitterness, or resentment just as my neighbor needs to search theirs for prejudice or unhealthy ethnic pride. In my fight for equality I’d forgotten one thing: I would not be called to give an account for their heart, but for my own.

In Conclusion, When I Recognized Race

Now, as a black Christian woman in a predominately white denomination (PCA), I continue to work out the implications of my race within this community to which I feel called. I do not take a race-blind approach to thinking about how I can serve, but rather ask how can the ways I’ve been formed by my experience as a black woman uniquely benefit the church and reflect God’s character. I ponder how my own journey to find a beauty hidden in plain sight might lead me to other beauty I otherwise may have missed.

Prayer Requests:

- For black Christians in predominantly white spaces to have an understanding of identity rooted in God’s sovereignty and goodness.

- For healing from past pain around racial difference inflicted by family, friends, or strangers.

- For the holy imagination of the majority culture to value diversity as much as the God who created it.