As a believer in Christ and a professor of American history, there is no greater teaching dilemma I face than that of Slavery and Scripture. At times, part of me dearly wishes there were an eleventh commandment in the Bible that says, “Thou shalt not own slaves.” That would make my job a lot easier. With such a commandment in hand, students and I could simply condemn slave-owning Christians, including evangelical heroes such as Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield.

But as sensitive students of Scripture have noted for centuries, there is no such eleventh commandment. Instead, there are household injunctions regarding the behavior of masters and slaves (Ephesians 6:5–9; Colossians 3:22–4:1). In the Pentateuch, there are laws about Israelites and their slaves, and the anticipation of a jubilee year in which slaves would be freed (Exodus 21:1–17; Leviticus 25:35–55). There is the exodus delivery of enslaved Israel from their Egyptian masters, and there are repeated prohibitions against “manstealing,” or kidnapping people and forcing them into slavery (Exodus 21:16; Deuteronomy 24:7; 1 Timothy 1:10). Then there’s the stirring note in Galatians that “there is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” This truth is applied to all those who are “baptized into Christ” (Galatians 3:27–28), which suggests that Paul expected slaves and free people to be treated equally in the body of Christ, at least with regard to baptism and other church practices. But we never quite get an indisputable ban on slavery itself.

As Christians who hold a high view of the authority of Scripture, we believe that the Holy Spirit inspired every single word in the Bible. This implicitly means that he inspired the biblical authors to not say other things. The Bible is perfect in its parts, and perfect as a whole. We believe that every command, every historical account, and even every topic not covered resulted from the Lord’s sovereign design. But just as we may not understand what we’re supposed to gather from every passage (say, the story of the medium of Endor in 1 Samuel 28), we may not understand why the Lord did not include more explicit instructions about topics that seem awfully important.

Pro-choice critics might note, for example, the absence of a direct prohibition on abortion in the Bible, even though for pro-life Christians the ethical inference is inescapable from passages such as Psalm 139:13–14 (“You knitted me together in my mother’s womb”). Slavery is a similarly perplexing example. The practice of slavery has been one of the great moral abominations in history. Why doesn’t Scripture denounce it directly?

The lack of comment of Scripture on the evil of slavery itself may not become fully explicable to us in this life. It is hardly a cop-out to remind ourselves of the Lord’s caution to his people in Isaiah 55:8: “My thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways.” Yet there remain some caveats that can somewhat mitigate our perplexity on the matter. One is that the Scripture does attack certain essential aspects of slavery as practiced in ancient Greece and Rome. Another is that at the time of the New Testament letters, Christians could hardly imagine changing the laws of society at large, since they were a small and often-persecuted sect that many outsiders regarded as a bizarre cult. Few could have imagined a post-Constantinian order in which Christian morality became the law of the land.

First, the Old and New Testaments do forbid practices that stood at the heart of the institution of slavery in its ancient and modern forms. Aside from the general prohibitions on wanton violence by Christians, the most obvious stricture was that against the practice of “manstealing,” which is condemned in Exodus, Deuteronomy, and 1 Timothy. Manstealers were human traffickers who kidnapped people in order to sell them as slaves. Manstealing was a known but prohibited practice in the ancient world. It was more common among slave traders in early modern West Africa (both Africans and Europeans), if only because of the larger scale of the Atlantic slave trade.

English translations use a variety of words for Paul’s term “menstealers” (KJV) in 1 Timothy 1:10, including the English Standard Version’s broad rendering of it as “enslavers.” If Paul here meant not just to indict kidnappers, but slave traders generally, that prohibition would have condemned much of the original circumstances of enslavement in both ancient and modern slaving economies. It would not have touched the status of those born into slavery, and African Americans born into slavery became the norm after the United States banned further imports of slaves in 1808. Yet it would be hard for any slave owner to plausibly suggest that he had nothing to do with slave trafficking, especially if he had ever bought a slave at auction.

In a more subtle move against slavery, Paul denounced extramarital erotic encounters, including same-sex liaisons and recourse to prostitutes, in passages such as Romans 1:26–27 and 1 Corinthians 6:9–10. For Paul, these sorts of nonmarital encounters represented porneia, or fornication, and they were strictly forbidden for Christians. When you realize, as Kyle Harper demonstrates in his book From Shame to Sin, that ancient world same-sex encounters were commonly between a free man and a male slave, and that prostitutes were often enslaved women, it becomes evident that Paul was forbidding sexual behavior that was essential to imperial Roman slavery.[1] Going to prostitutes, and sexually preying on male slaves, was common and not shameful in pagan Roman culture. But Paul was saying to the new Christian churches that they should not countenance such behavior among believers. Especially in the uninhibited sexual climates of Rome and Corinth, telling people not to engage in homosexual acts and not to visit prostitutes was close to condemning what slavery itself entailed.

The New Testament’s ethical codes tended to assume that the world was fallen and deeply hierarchical, and those codes carved out an alternative sphere of holy living for believers living as strangers in that world. Many in the ancient Roman Empire found Paul’s sexual ethics nearly unfathomable, partly because they fundamentally challenged the sexual norms of a slave-based society. The church’s situation changed dramatically after the conversion of Emperor Constantine in the fourth century AD, when suddenly Christians could imagine having a dominant influence on the mores and laws of the empire. That set certain Christians to thinking about slavery in a more comprehensive way. Indeed, Constantine himself legally expanded the power of churches to emancipate enslaved people in a congregation.[2]

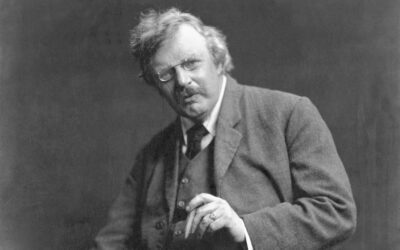

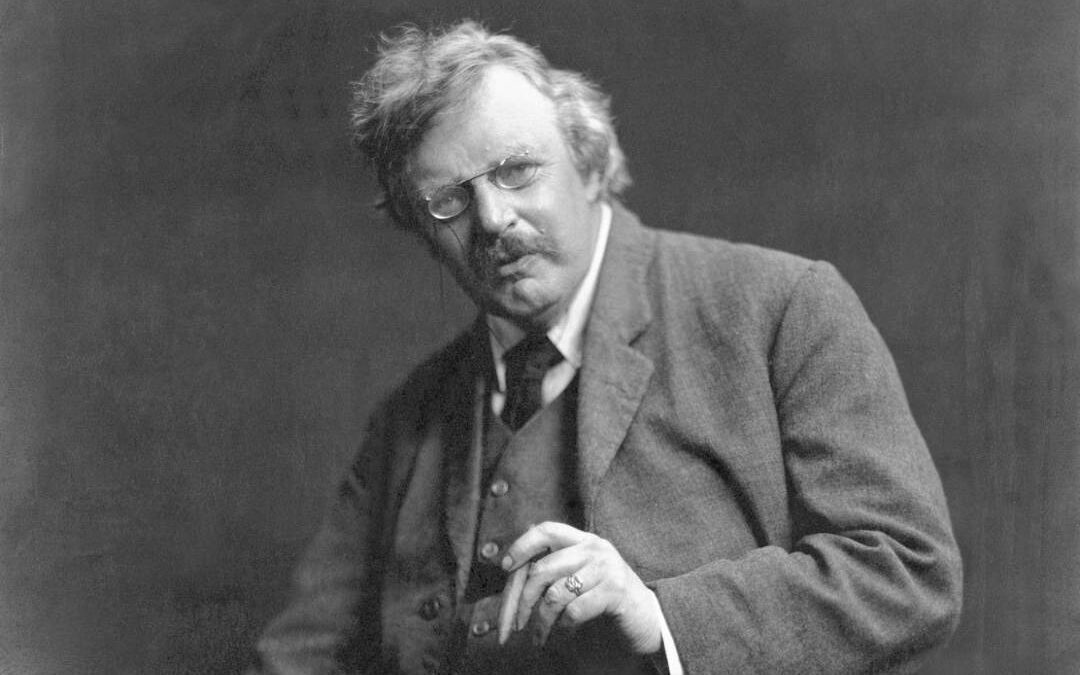

The Bible may not give us that elusive eleventh commandment, but given the bent of the Bible’s ethical codes, it is hardly surprising that one of the first writers—and perhaps the first writer—ever to challenge slavery as an institution was not a pagan Greek or Roman, but a Christian church father, Gregory of Nyssa. Gregory, born around the same time as Constantine’s death in the 330s, raged against the sinful presumption of enslaving people created in the image of God. “If God does not enslave what is free, who is he that sets his own power above God’s?” he wrote. As Kyle Harper notes, it is “no small distinction to be the earliest human to have left an argument for the basic injustice of slavery.”[3]

This welcome development—a Christian argument against slavery itself—was a natural outgrowth of the ethics of the Bible, the doctrine of the imago Dei, and the beginnings of Christian thought about what a post-pagan Christian society might become. Christian thought was never uniformly antislavery, of course, until long after legalized slavery vanished in the 1800s. But the sources of antislavery thought were always powerfully Christian. And while Scripture doesn’t speak directly against slavery per se, it does condemn grievous sins that were integral to slavery as practiced in the ancient and modern worlds.

This is an adapted version of an article which was originally posted here.

- Kyle Harper, From Shame to Sin: The Christian Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 26–27. ↩

- Noel Lenski, “Constantine and Slavery: Libertas and the Fusion of Roman and Christian Values” in Atti dell’Accademia Romanistica Costantiniana XVIII, ed. S. Giglio (Perugia: Aracne, 2012), 251.↩

- Kyle Harper, “Christianity and the Roots of Human Dignity in Late Antiquity,” in Christianity and Freedom: Historical Perspectives, ed. Timothy Samuel Shah and Allen D. Hertzke (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 1:134. ↩

Prayer Requests:

- Lament that humanity finds so many ways to dishonor God and each other.

- Thank God that slavery in our country is over.

- Pray that God would increasingly bring about justice in our land.