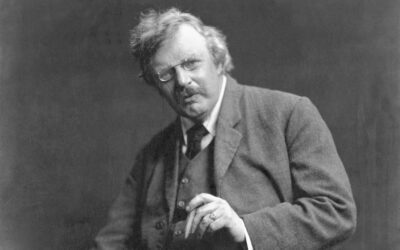

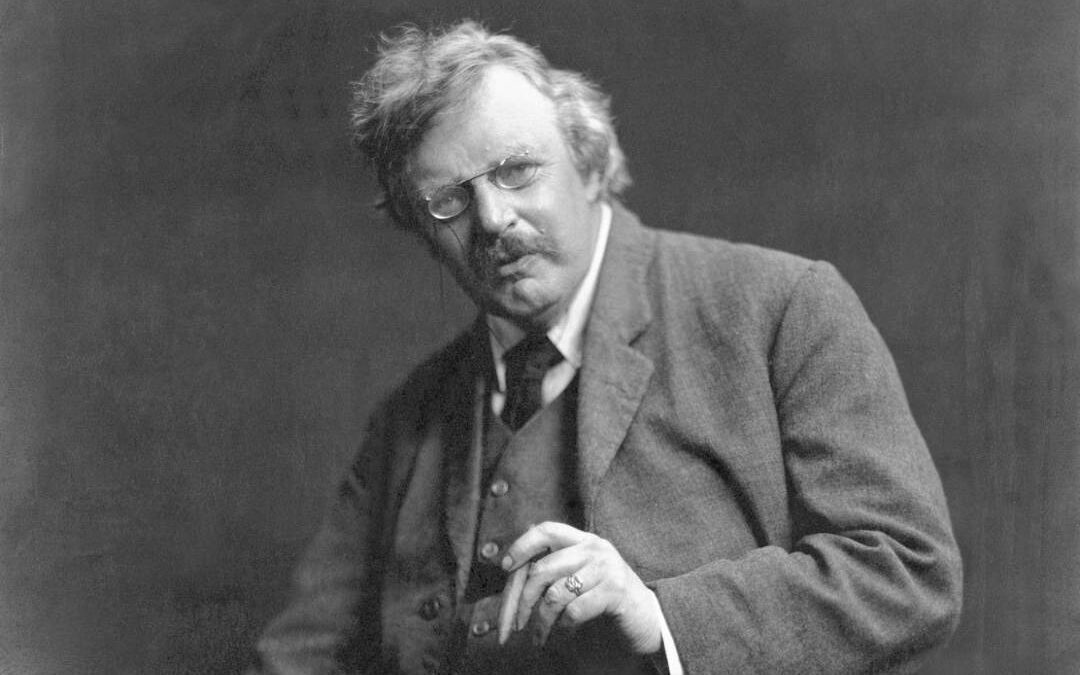

Although it has largely been forgotten in the century since his death, the great Dutch Reformed theologian Herman Bavinck (1854–1921) was a prominent Christian voice against racism in America in his own day and age. Following a journey to North America in 1908, he gave lectures around the Netherlands critiquing a society built on the labor of enslaved human beings that could find little to heal the deep wounds of racialized hatred.(1) Bavinck’s lectures on race could be apocalyptic in tone: in them, he openly pondered whether racism would soon lead the American experiment to fail outright.

One of the most striking features of his perspective on race is the effort to understand more of the African American experience by listening to African American voices. It is clear from his notes during this trip, for example, that he had read W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington and was not content simply to let white Americans form his impression of their African American neighbors. The reality of experience mattered too much for that.

As such, the mature Bavinck’s theological instincts are fascinating: the same figure whose Reformed Dogmatics contains a breath-taking section on the human being as the image of God also thought it necessary to pay serious attention to the experiences of those human beings in the world. Elsewhere he once noted, “Old Testament morality is written from the point of view of the oppressed.”(2) Theologically, Bavinck believed that experience matters. While he certainly was not a Liberation Theologian in the mould of, say, a Gustavo Gutiérrez or a Leonardo Boff, his mature perspective was that orthodox theological instincts go hand-in-hand with social concern. In that light, his regular refrain on the gospel as good news for the entirety of our human existence would be a fairly meaningless one if it said nothing to address the experience of racism.

In Bavinck’s own life, though, that perspective seems to have been one that developed over time—and that was notably underdeveloped as a twentysomething theology student. In the summer of 1880, for example, Bavinck defended his doctoral dissertation (on the Swiss Reformer Ulrich Zwingli’s theological ethics) at Leiden University. His close friend Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje (1857–1936), a radical skeptic who later converted to Islam, also defended his doctoral thesis that year. Writing to Snouck on his performance in the defence, Bavinck was concerned that his friend had defended Judaism (as a religion)—in the face of anti-Jewish writings of German Catholic theologian August Rohling (1839–1931)—in a way that risked relativizing Judaism’s theological differences with Christianity.

To the twenty-six-year-old Bavinck, the key priority in such a discussion was the meticulous comparison of truth claims more or less in abstraction: although the young Bavinck saw theology as a real-world concern, at that point in his life, to talk about Christianity vis-à-vis Judaism was to talk about “difference in principle.”(3) It is worth noting, of course, that thus far in life, his own immediate experience of Christian-Jewish relations had been one of peaceful co-existence: shortly before he registered as a student at Leiden, the university had appointed its first Jewish rector, Joel Emanuel Goudsmit (1813–82). In 1880, the young Doctor Bavinck was living in Kampen, a town that had been home to a settled Jewish community for centuries and where Jews often attended public events held by the local Christian Reformed Theological School.

In that context, Bavinck had not yet been prompted to think more deeply about difference in experience alongside difference in principle. That prompting came, however, in Snouck’s reply to his critique. At this point, Snouck was living in Germany where he had come face-to-face with the simmering anti-Semitism that would soon give rise to the horrors that marked the twentieth century. It was a world from which both Bavinck and Snouck seem to have been sheltered in the Netherlands. Snouck wrote,

You did not appreciate that I took on the task of protecting the Jews against the unfair, unseemly and not infrequently dishonest, but almost always untrue acts of accusation that people especially in Germany now fabricate against them . . . . If I understand your way of seeing the relationship between a modern Christian and a Jew, you prioritise the distinction between them, at its core, in abstraction, and you wanted to see me stick to that abstraction, yes, even that I would make a pronouncement on it, when actually, there was not the least reason for this. I was opposing, sincerely, the German (political as well as religious) movement against the Jewish race.(4)

In essence, the issue of race was putting lives at grave risk, for which reason Snouck rebuked Bavinck for dealing with the question of “Christianity or Judaism?” as a task to be met first with abstract apologetic precision, when in fact, anthropological concerns raised the more urgent need. Bavinck was told that his theologizing needed to be accompanied by attention to “social economics and politics” because the Jewish experience in Germany was unlike Christian experience.(5)

To Snouck, the young Bavinck needed to learn to think more clearly about theology, experience, and race. Perhaps the most striking part of Snouck’s response is the direct reminder that Bavinck’s experience of Christian-Jewish interaction was limited to the Netherlands. “I am convinced that indignation would rise up within you,” Snouck wrote, if Bavinck were to gain first-hand experience of German anti-Semitism.(6)

It does seem that as he matured, Bavinck paid heed to Snouck’s challenge. His American critiques suggest as much. To add a further example, the mature Bavinck shocked some of his South African students—supporters of what later became apartheid—by telling them he would be happy for one of his descendants to marry a Zulu, as long as they shared the same Christian faith. One of his South African students, Bennie Keet, later became a prominent anti-apartheid activist. In Bavinck’s classes, theology and social concern were no strange bedfellows.

It is certainly not the case that Bavinck provides us with the last word on race. However, for Reformed Christians in 2021, he has much to offer in prompting us to think more carefully about the relationship of theology to both race and the experience of it. If anything, he serves as a timely reminder of the nature of the Reformed tradition’s twin commitments to doctrine and ethics: whatever we say about the image of God in abstraction can never remain an abstraction. Doctrine must shape life. These vertical and horizontal concerns may have been set on different tracks, and reimagined as opposing forces, in the later twentieth century divergence between fundamentalism and the social gospel movement, but Bavinck reminds us that it was not always so. And as such, he offers today’s Reformed Christians an example of what it might look like to maintain a dual commitment to their orthodox faith and its social dimension.

Beyond this, he provides an important reminder that when their black brothers and sisters speak about the experience of racism, white Christians should listen. Bavinck read Du Bois. A century on, white Christians have no shortage of opportunities to listen to similarly articulate voices in our own day—voices to be listened to openly, attentively, and not defensively. Bavinck’s example reminds us that doing so does not compromise your orthodoxy. In fact, it might help you work out how to express it more faithfully.

(1) James Eglinton, Bavinck: A Critical Biography (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2020), 247-50.

(2) Herman Bavinck, ‘Christian Principles and Social Relationships,’ in John Bolt, ed., Essays on Religion, Science, and Society (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 126.

(3) Jan de Bruijn and George Harinck, eds., Een Leidse vriendschap: De briefwisseling tussen Herman Bavinck en Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje, 1875-1921 (Baarn: TenHave, 1999), 75.

(4) De Bruijn and Harinck, eds., Een Leidse vriendschap, 78-9.

(5) Snouck provided two key reasons: first, the Jewish experience was one of oppression; and secondly, the great difference between being Jewish and being Christian (in Snouck’s eyes) was that Christian identity contains no ethnic component and can be cast off at will by those who profess it. By contrast, Snouck wrote, a Jew is “someone from a particular ethnic group” whose identity remains such, regardless of that individual’s nationality or views on religion. It cannot simply be discarded: even if a person renounces their Jewish identity and belief, in the eyes of the anti-Semites, their Jewishness is indelible.

(6) De Bruijn and Harinck, eds., Een Leidse vriendschap, 79.

Prayer Requests:

- Praise God for prophetic voices like Bavinck from which we can still learn

- Pray for insight to see the world around us as God sees it

- Pray that Christians would seek justice for all, even when it doesn’t immediately serve our own interests